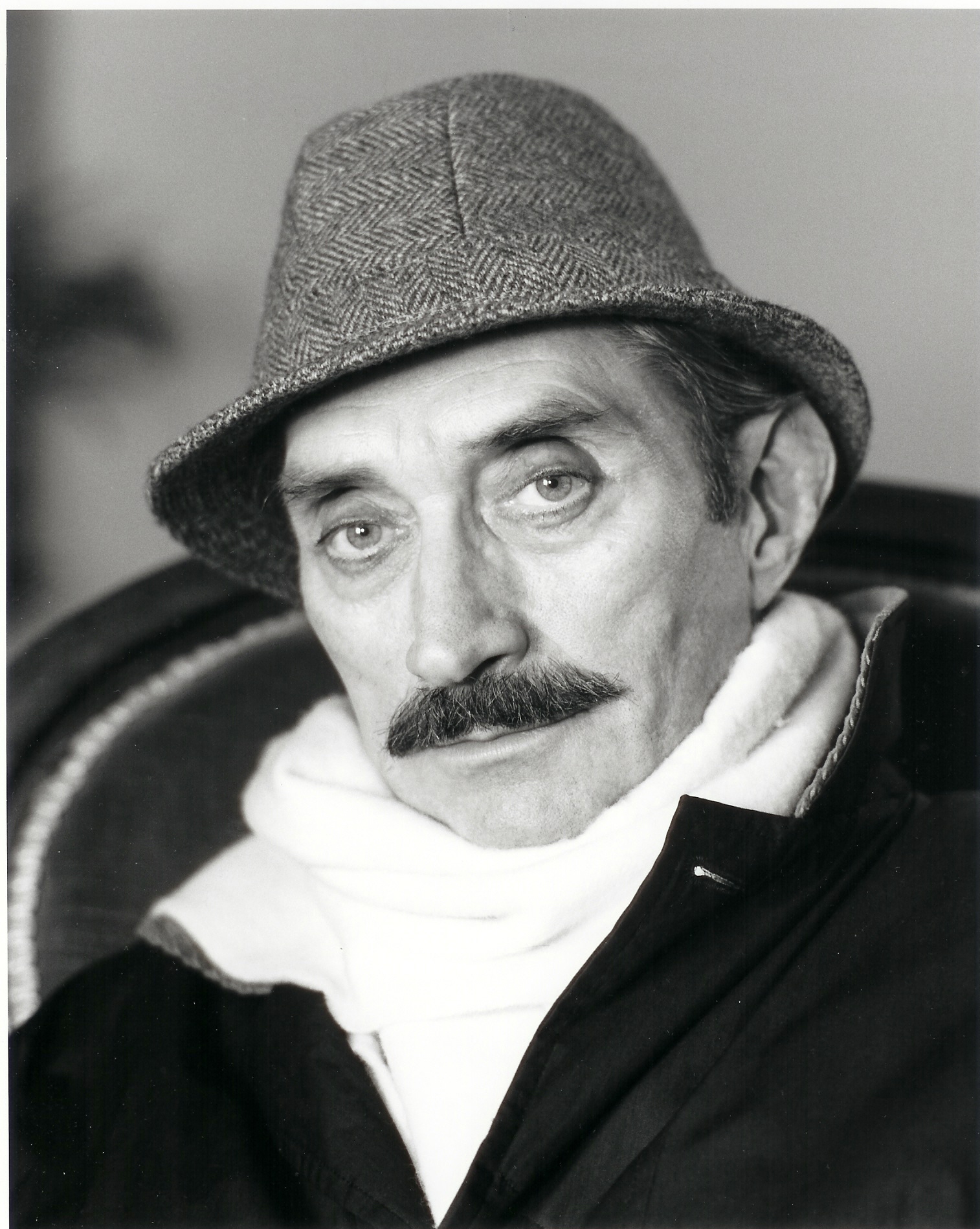

The Eyes and The Voice

The Memoirs of Vladek Sheybal

1923-1992

* * *

Chapter One.

Vladek's House

Fulham, London circa 1991.

Sorry for my chaotic talk. Funny, I am looking now at my painted cupboards in the kitchen. I painted them a sort of orange-red with some flowers on them. My kitchen looks very Polish; my house in London is very Polish too I think. My mother once said when she came to visit me that it's a little replica of our country house in East Poland, Ukraine as a matter of fact.

My thoughts have to go back into my paradise, into my childhood - it was so happy. Otherwise I wouldn't be able to survive this asylum, this exile, this situation - it would be too difficult. Now everybody I loved has gone. My parents are gone, my beloved sister, Janka has gone. I will never forget them.

I remember the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto. I remember it vividly, because it was the time in which I had to go to my acting classes in our 'underground' college, which took place only in private apartments, like the old studies in Warsaw were aonducted in private apartments. It was inthat part of Warsaw, which was far away from the centre. When the ghetto uprising started, the tram which ran next to one of the walls of the ghetto had to stop before it reached the ghetto itself because the Germans were shooting at the ghetto. Jewish people, who were taking part in the uprising, were shooting back at them from the ghetto too. This meant that people had to walk quite a long distance, at least one and a half miles around the outside of the ghetto, then board another tram on the other side of the ghetto - which would take people to this district where my classes were being held. The atmosphere in Warsaw was very grim and depressing, and the people of Warsaw really went through hell with this uprising. The Germans were fighting street after street, house after house, burning the Jews and killing them. It had a tremendous affect on us. We were completely helpless - we couldn't do anything at all. The Germans brought in tremendous amounts of arms, and completely surrounded the remnants of the Jewish ghetto. Some of our Polish boys were fighting arm by arm with the Jewish people there. One of them was Urick Zelfan - a great friend of mine, who killed himself when he didn't have any choice to escape; a typically Polish gesture, ridiculously fantastic but also chivalrous and tragic. When the uprising was just ending its tragic existence, and shortly before he died Urick pulled a few Jewish friends out of the ghetto, taking them as far as The Povonski Cemetery in Warsaw, trying to save their lives as well as his own. Once they reached the cemetery they were to be redirected to some private apartments, or the forests outside Warsaw to join the Polish Partisan army. Suddenly they realised they had been surrounded by the Germans, who knew about certain people from the ghetto running away to the nearby cemetery and then on to further destinations of safety. They started shooting at him and he was shooting back. Finally he shot out his last bullet. He didn't have any more bullets, so he just took the gun of his Jewish friend who was standing next to him and said.

“Shoot me.”

“No, I can't do it” his friend replied.

So Urick shot himself - just like that.

Strangely enough, Urick's Jewish friend survived and later on the story trickled into our family. My mother adored Urick. I met Urick's parents in London later on and I told them his story. They only knew that he died, but they didn't know the circumstances. So he died like that.

The whole of Warsaw was absolutely horrified by this uprising and all our lives became subject to what was going on in the ghetto. First of all you heard shooting all the time, then you smelled burning houses and burning bodies as well. A huge dark cloud of smoke filled the whole of Warsaw giving us a reminder of what was going to happen to us, and indeed it did happen, a year later the Warsaw uprising started. It lasted 63 days, in which the whole of Warsaw was then almost completely destroyed. The Polish Underground army had an agreement with the Russian army which was already on the outskirts of Warsaw - when we started the uprising, the Russians stopped advancing. The playing of music was cancelled, parties were cancelled and people were praying for the Jews in the Churches. In their incredibly sadistic way the Germans built two 'merry-go-rounds' at the side of the ghetto. They wooed the children with sweets to get on, the music was playing and the happy children were going round and round on the roundabouts. When the parents tried to take their children off the merry-go-rounds, the Germans threatened to shoot the children. It was all absolutely ghastly. Obviously the Jews heard this merry music outside. God knows what they were thinking. Some of them most certainly were thinking that we on our side, were enjoying them dying in the ghetto!. In order to counteract this kind of German sadism, the Polish people, women especially, built lots of little altars all around the ghetto and masses of people came to kneel in front of these altars and pray. Priests came too and were giving mass. People were singing songs, church songs and psalms as a way of encouragement to the Jewish people in the ghetto as a way of saying that we think about you, and we are praying to God for some kind of miracle. The Germans tried to stop it all but then they gave up. The merry-go-rounds were dismantled too. I had to be there three times a week because of my travelling to classes. Life had to go on. The show has to go on, we say. We've got to get on with life in spite of the ghetto tragedy. This was especially true when we knew that the next turn would be ours, and indeed it was. So this is my little tragic account about the ghetto uprising - my recollection of what I have seen myself, and I have to add a little episode which has imprinted itself on the core of my brain. One day travelling to my classes I stopped at one of these altars, to kneel down and to pray with the people for a miracle for the Jewish people. Suddenly in one of the windows in one of the burning houses inside the ghetto (I think perhaps it was the fourth floor), I saw two people; a man and a woman. With a tremendous yell, and holding each others' hands they threw themselves down into the flames and certain death. We all gasped. A year later, during the Warsaw uprising I saw similar scenes happening in Warsaw. We are linked with the Jewish people in this incredible inhuman martyrdom of dying - for what? For black and white? For Jew and non-Jew, or Catholic and non-Catholic? I never understood it. I never will.

I see today is 11th February (1990?). Anatol Sharanski has been exchanged to the West on the bridge in West Berlin, and flew to Frankfurt to join his wife who hadn't seen him for 12 years. Then he flies on to Israel, as a symbol, as a hero and as a human being as well. I feel very deeply moved, and I can understand his feelings of being deeply moved when I saw him on the television screen. A kind of diminutive man with clothes much too big for him, he was smiling but it was a strained smile. He was walking into the free world after years of gulags; after having been a prisoner and a harassed man in the Soviet Union.

Within a few hours (it can only happen nowadays with modern techniques) he's whisked from this cold winter and snow of the gulags and Russia into freedom. Into a warm country, into Israel. They wait for him there in his new home country. I thought how I felt when I walked from my concentration camp during the war and into freedom. Then how I felt the second time when I left my country in 1957. Away from communism, away like a mad man and how I felt when finally my train crossed the border between Czechoslovakia and Austria and into freedom. I know exactly how he must feel. Very moved. I am very happy for him. For this development. For Anatol Sharanski. Then, as he walked from the plane in Israel led by his wife, onto the tarmac of Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv (which I knew so well), his face already was kind of having a colour in the shape of the sun. He was turning into the sun. Sun came into his life.

My kitchen downstairs in my house in London has a very intimate atmosphere with this red lamp on the table, my cardigan drying above the radiator and here I separate myself from the world by drifting into this kitchen. Whenever I walk into my kitchen, I walk into some friendly surroundings. This is not just a kitchen, but a space which has become broken into positive fragments. The image of the concentration camp has gone. I don't know. My kitchen has become something special, a new world for me, funny.

Vladek in his kitchen with Donald Howarth's Jack Russell - "Rumi."

* * *

Chapter: Two

Halina Dohotska and her sister.

Both were Jewish ladies, and both women survived the whole of the German occupation and they were always smiling, always looking very elegant and beautiful. They were living in the same apartment that they both had before the war in Godgera Street, not far away from where we were. Everybody in the street knew that they were Jewish and nobody ever moved a finger to harm them. Halina would be coming into our flat to talk to my auntie Sophia, who used to be a singer, they were very close friends, doing their shopping in the little shop which was just round the corner. One day while getting drunk, our caretaker started threatening my father, saying that he knew there were lots of Jewish people staying in our flat and started threatening the security of Halina Dohotska and her sister as well. My father was very angry with him. “Please I advise you first of all not to get drunk” he said, “secondly not to talk about these things, because you know what the reaction of our underground army will be … it could become dangerous for you.” The caretaker got a bit frightened, but after a while he got drunk again and again started threatening us as well as Halina and her sister. My father decided to convey this to our underground army and one morning we learned the corpse of our caretaker was lying in the field nearby. On his chest was a piece of paper which stated that he was executed because he wanted to denounce the Jewish people. After this execution, of course, there was the fear that the Germans would come and round up our district and start taking us one by one for shooting. After two days the body disappeared. Apparently our resistance army wanted to make a kind of spectacle of him, and also give out a warning to all other possible denouncers of the Jewish people. Then they removed his body in order not to endanger the whole district. Years later, in my flat in London, Halina told me that she was also blackmailed by a Jewish friend of her father.

In 1939 with the beginning of the war, everything collapsed and the whole world went dark.

Here I am, again in my capsule, my kitchen with the lovely glow of this red shade on the lamp and whenever I have to go upstairs, with every step up, I feel I'm reaching freedom. I'm going out of my concentration camp. It's a funny feeling, I already condemned myself again in 1986 in February, again to the concentration camp, to imprisonment and to this awful inhuman experience of not being able to be an individual. These were the Dark Ages for me, but in the end, what ever matters is what is inside us. I think you can always carry it with yourself as I did. Now I understand how much I did carry with myself, my own sense of justice and independence.

All the professors of our college in Krzemieniec were being arrested by the Gestapo and shot, executed. The Germans were getting rid of the Polish intelligentsia from a list prepared by the Ukrainians. My father was not on the list, thanks to his very humanitarian attitudes towards all minorities and especially towards the Ukrainians. So the Ukrainians showed their gratitude towards my father by not putting his name on the list, but they warned him and he had to leave Krzemieniec. He lived in hiding with some friends in the country.

* * *

Chapter: Three

The Warsaw uprising started 1st September 1944. I will always remember this moment and this day when I saw from the balcony of our flat a girl, her name was Oscenia. She was pointing to something first left, then right with her hands going like a sort of windmill as though she was directing traffic. The shooting had started. It appeared that the girl was from our resistance army who was really pointing to certain people, where they should go, in which direction, and in which street and whatever. And then Warsaw went through 63 days of hell, 63 days of desperate fight. We were utterly powerless - not having enough arms and being constantly bombed by German planes. They were flying very low, almost laughing at us and simply dropping their bombs. At the same time the German artillery destroyed houses, and these awful new weapons; we were calling them mooing cows. They were making this incredible noise like 200 or 2,000 or 2,000,000 cows and then spitting out about 30 or 40 mines or bombs which were falling onto three or four blocks of flats at the same time, and destroying them completely. Towards the end of this 63 days I was desperately looking for some medicine for my father who was very very sick in the cellar, literally dying. He had typhoid, he was dehydrated already, his tongue was hanging out of his mouth and my mother was praying. Her face was white and in her eyes was a beautiful expression which suggested the only hope and justice is in God. I went to another district of Warsaw where there was a doctor friend of ours, to get some medicine for my father. The only way to get there was to climb the mountains of rubble in the streets, take a chance on being burned by the fire from burning houses on both sides of the streets, and run across squares which had Germans shooting from both sides. There was no choice but to run and hope that no bullet was going to hit you. Finally, you would have to go down into the cellars. Warsaw became like a rabbit warren underground, and down in these cellars there were signs for the streets above. There was a complete underground city. Certain streets could be reached by the trenches which were built under the streets. Finally I found this doctor who I hoped would give me some injections for my father. Suddenly, out of the blue, I was caught by the Germans who appeared from a doorway of one of the houses. That is what street fighting is all about. We were here, Germans were there. We were around the corner here, Germans were round the corner there. It was all very flexible and interchangeable, constantly. When I was caught by the Germans I was shifted along with another 200 people who had already been collected, we were all being kicked and hit by their rifles and guns. The Germans were always shouting and making incredible noises. More crowds caught, people appearing from left and right like rivers, into one big river. After a few hours of this senseless run with the Germans pushing us like cattle, we stopped on a big plain in the centre of Warsaw. A huge student house dominated this plain. It had been a student's house built before the war but during the Warsaw uprising it was turned into Gestapo headquarters. This huge plain was covered with grass and streets were all around it. You could say it was a square, but it wasn't a square, the only description is a plain. There were already thousands of people caught in Warsaw and of course some of them were in an awful condition. Some of them were wounded and some carried parcels, possessions. Some of them didn't have anything, like myself. We were all instructed through loudspeakers (in Polish) to sit down on the ground and wait. We knew that outside Warsaw there was already a kind of transitory concentration camp for millions of Warsaw people and here I am going to make a digression:

During the 63 days of the Warsaw uprising, half of the population was killed or burned. Warsaw counted two million inhabitants before the uprising and one million inhabitants were killed during those 63 days.

We knew that we would be selected but of course we didn't know our fate, we didn't know what they were going to do to us. According to some stories coming out of Warsaw (which was looming in the distance and was full of smoke), we heard tales of fires, shooting and explosions and people dying - and here on the German side, perhaps just one mile away, we were sitting on the grass in the sun and waiting. It was September and it was very very hot, not a cloud on the sky. Unfortunately, like in 1939 the whole sky was cloudless and therefore German planes could absolutely ravage the skies and the ground, throwing death with their bombs everywhere, without anyone or anything to stop them.

Radar had not been invented then or wasn't known, so the only times there was no bombing, during the Warsaw uprising in 1944 or at the start of the war in 1939, were the nights when the planes couldn't fly. We knew that eventually we would be taken to Prushkov, a big transitory temporary concentration camp and from Prushkov, God knew what was going to be our fate. I was sitting on the grass and kind of looking around taking in a little bit of sun, but my heart was very much in Warsaw. I was thinking about my parents, especially my father. I was absolutely sure he didn't have any hope to live. I was looking at this blue sky and then I was looking at the sea of heads, at the people. Somehow I don't remember if people were crying or talking. We were all sitting in silence, an apocalyptic silence. It was the silence which moved me so much, there was a closeness in it. This silence was already sculpted by the powerlessness and hopelessness of our situation. There wasn't any room for tears anymore, there wasn't any room for words anymore. There was only room for beating hearts and for thoughts, and perhaps for fear, though I don't think we feared very much. We went through such hell that fear didn't exist anymore in our hearts - rather keep your head straight and show this to these Germans that you have a style and your dignity. I was looking at this big house so far away in front of us with the big steps leading to the middle of the big wooden prison-like gate; it would open and close from time to time. It all looked to me like a Fellini film: The entrance to heaven or the entrance to hell. Behind this gate were the headquarters of the Gestapo, and there were a few Gestapo soldiers standing on these huge steps with rifles at the ready, watching us - this silent crowd of slaves who were waiting for God to make the little sign with his big finger, and determine what would happen to us. As I was looking at the house I suddenly had a very strange feeling as if my thoughts were detached from me, as if they flew out of my head and went forward to this big gate, because there on these steps was standing a person, a Gestapo officer with a big dog. The officer looked at all of us. He couldn't possibly have thought about seeing me or spotting me, this little tiny speck somewhere in the middle of this crowd, and yet my feelings and my thoughts jumped up out of my brain and hit him. There was a kind of strange and frightening vibration which went from him into myself and hit my heart too. My heart stopped beating and I stopped breathing for a second. I got frightened for the first time and I didn't know why. An uncanny feeling. Similar things have happened in my life before and I decided not to provoke anything. Anyway he was so very far away, he was a tiny little figure there in the distance by this huge gate to hell. And yet I realised that I had to look at the grass, I had to look at the earth underneath me. I shouldn't send any vibrations towards this person because he was going to represent doom, the fate in my life. He was going to become somebody important in this very moment, in what way important I couldn't fathom, but he would change my life. Something was going to happen because of him. After looking at the grass for another hour or perhaps two, like an empty inanimate object, I looked up once again and I saw this Gestapo officer with his dog already inside the crowd of people. He was stopping, looking at everyone as if he was looking for someone in particular. The dog sniffed the people too. The Gestapo man asked some people questions and I saw them handing him their documents. He would read them, and then give them back to the people. With tremendous trepidation and fear, I realised that he was walking nearer and nearer to me and I knew something was going to happen. I knew he was my fate. Another half an hour of agonising waiting; I began talking myself into not being afraid. Stubbornly I looked at the grass and the earth underneath me, trying to take the freshness from this nature into myself but I was already paralysed with some kind of strange uncanny fear. Suddenly I heard the dog sniffing very near me. I didn't dare to look up and then I saw the big black boots stopped next to me. Then I had to look up and this man was standing above me and looking at me, holding the dog on the leash and the dog was looking at me as well. “Can I have your documents - Kenkarte?” he spoke in perfect Polish. (Kenkarte was the German word for document). A quick thought: In my photograph I had no spectacles, I handed him my Kenkarte and I took off my spectacles. I remember that when the Germans were pushing us in front of them through the streets of Warsaw, a few hours previously, I had put on my spectacles. I had been short-sighted all my life and I wanted to see the whole horror of destruction of Warsaw and to see the faces of the people, to be witness of this apocalyptic inhuman scene. A scene from hell, from Dante's hell, a scene which was all in grey and black; there was no other colour. The Gestapo man looked at me.

“It doesn't specify in your Kenkarte that you wear glasses as well.”

“No it doesn't” I said.

“Why doesn't it?”

“Well, simply I didn't have glasses then, I started wearing glasses quite recently.” “I see.”

He handed me back the Kenkarte and he said to me, in a kind of very detached way: “Will you please get up and go to the main gate.” He pointed at the big house and the huge gate - to heaven or to hell , already looking at the other people, victims that he might prey on. He didn't repeat his instructions and moved on. I understood every single word and my stomach turned, my heart sank. I got up and I saw the other people looking at me with compassion. The orders were in the air, the orders were inside me. I thought I could do something, I could kill myself now for instance, because I had been arrested, and yet I was like a stupid idiot going through the crowd of people sitting down on this green grass, to this big gate and I am going to be singled out and perhaps shot or killed or tortured, or whatever. Of course, I didn't know what all this was about - with the Germans you never knew. You never asked them what this was all about, you were a Pole and that's that. That was the accusation; like being a Jew. I stopped by the gate. The Gestapo soldiers who were standing there at the ready didn't even look at me, and I was the only one on the big steps standing by the door facing the whole plain with the crowd of people from their side - from the German side. Now I understood my fears. I was afraid that I should look at the whole scene in reverse, like in the mirror and here I was on these steps, standing - the only person there, except for these Gestapo soldiers. I was facing the whole scene from the German side, from the German point of view, sort of like Jesus on the cross already. I stood there for about an hour perhaps and then I saw him - this Gestapo man with the dog coming back very slowly and deliberately. He made a sign with his fingers to his Gestapo soldiers, one of them saluted him and yelled:

“Heil Hitler.”

Then he opened this big gate and my German Gestapo officer pointed at me, gesturing at me to step inside.

I went inside the courtyard and the big gate closed behind me. This was the end of my life, I thought. I had been parted from my people with my likes, with my soul, with my blood, with my Warsaw, with my everything and here I am on this fearful territory which is German Gestapo territory. The officer with the dog was standing near me, he never looked at me properly, he was just treating me like an object. He spoke to me in Polish again, looking at the wall, not at me.

“Would you follow me please?”

So I had to follow him.

There was this big courtyard and there was some kind of little wooden shed in the middle of it. He led me across the courtyard to the side door leading to other floors and offices. I could hear the typewriters and some muffled German voices inside the house. There was nobody in the courtyard except for a woman and a man sitting on the steps by the entrance to the side door. My Gestapo man left me there by the entrance. He walked inside the house and here I was looking up at the blue sky with my heart already stopped beating, knowing that this presumably is the end of everything in my life. I had already said goodbye and I remember that I had a thought - I was very near a wall. If I jumped the wall, there were houses on the other side with no people in them. In this part of Warsaw there were no people because they had been thrown out or evacuated, shot, killed or burned out already. Then if I start running … then came another thought - no, don't do it, because if you start doing something, immediately they will start shooting and obviously you are dead. I tried to stop my heart beating too fast. Suddenly this woman who was sitting there spoke to me, in Polish.

“Did you know him?”

“Who?”

“This officer.”

“No.”

“Ah” she said, “you have been arrested.”

“Yes.”

“We are not arrested” she said, “we - my husband and myself, we came here - we ran from the Warsaw uprising - we came here to meet our friend who works with the Gestapo, he'll help us to get out of here safely.”

I thought they must be these collaborators I had heard of.

The vast majority of the Poles were fighting the Germans fiercely, but of course there were some collaborators. She looked at me again.

“You are frightened, aren't you?”

“Reasonably” I said.

“I know” she said “you must be a Jew.”

I decided not to answer this question, what was the point?

“Ah, you see” she hissed, “you are afraid to talk.”

At that moment my Gestapo man came out without the dog and he looked at her, then he looked at me and he said again in Polish.

“Will you come with me.”

He led me to another door and up the staircase to the first floor. I saw the corridor with the doors and locks like in a prison, yes, it was a prison. He said something in German to one or two Gestapo soldiers who were guarding these doors and they led me to the third or fourth door. They unlocked it with a big clink-clonking sound - typical of a prison - and they pushed me inside a cell. Then the door was locked behind me.

Back to my kitchen in Fulham. The fridge is murmuring peacefully. The red lamp gives a nice warm glow, and yet - I feel scared. I have the urge to lower myself down to the floor and diminish myself to nothing. There is still in me this tremendous insecurity.

Fear.

If, at this moment, somebody knocked on the front door, I would presumably jump up with fear and yet I know I have this tremendous power - an invisible camera in front of me filming my close ups, my thoughts and feelings. That's how I went through all this experience without such fears. I was acting. Acting in a film ... constantly.

* * *

Chapter: Four

There were two men in the cell, one was a Yugoslav. How he got into this cell in Warsaw, nobody knows. The other one was a Polish man, he also avoided answering how he found himself in there. They were both frightened. They were both very typical prisoners, as I always imagined they would be - thin and unhealthy looking. There were two iron beds in this room. No mattresses, only wire mesh, but not the dense kind. There were big gaps between the mesh. There was no stool. There was one bucket which stank, which of course was for urinating and for defecating. Very soon I realised that the Polish man had severe diarrhoea. There was a peculiar little wooden box underneath the tiny window, which was quite high above the ground of course, with the iron bars. I tried to get on this box to reach this little window; although both men were angrily watching my attempts they didn't say a word. I had grasped the iron bars with my hands and I pulled myself up, I was on the same level as the lower edge of the window now. I could see the same plain where I had been sitting among the people about half an hour earlier. I could see the crowd of people following instructions from the Germans, getting up slowly and leaving. They were being pushed and hit by the Germans but they walked out slowly. They were transported to their next destination, a transitory camp in Prushkov near Warsaw ... from which ... who knows, perhaps Auschwitz might be the next destination. I asked my cell mates what our position was, and at the same moment I heard somebody start knocking gently on the wall, my cell mates started knocking back. Obviously they had been here for quite some time and they knew the prison language well. My men asked me who I was because they wanted to tell the people in the next cell. They were asking them about me. We've got a new prisoner here etc and I asked them again what's going to happen to us.

They stood up rather uncomfortably and said.

“Well tomorrow is our turn.”

“Our turn for what?” I asked.

“Well, they are shooting, executing cell after cell, we are in touch with all cells here. The previous cell was shot this morning, so tomorrow we've got to be prepared that they are going to shoot us.”

“What for?” I asked rather stupidly, “no trial, no nothing?”

They looked at me sadly and didn't say anything.

Suddenly I remembered that I had some little pieces of paper - the documents in my trouser pockets. They were showing my various names. Almost all Poles had their identities changed, and I also had some pieces of paper on me which I had used to register myself at certain addresses in Warsaw before the uprising, which also showed the different names. They might question me, tomorrow or even tonight. They mustn't find anything on me. I moved to the darkish corner in the cell and I carefully took out these pieces of paper. My cell mates didn't notice anything as I ate all the pieces of paper, I swallowed them up one by one. Somebody tried to open the door from outside. My cell mates told me that supper was coming and it arrived. It was some kind of soup. Later on when I was in the camp, I knew it only too well. It was water with a few floating pieces of white or red beetroot; no nourishment at all. They gave you a small piece of bread - one inch by half an inch perhaps, so we ate this. The Polish man started with diarrhoea again, he would sit on this bucket rolling left and right because of the pains. I think that he had typhoid, he looked as though he had a fever. There wasn't any paper to wipe himself off, so he did it with his bare hand.

My cell mates explained to me that the following morning the Germans would come in with either breakfast, or execution orders. If the latter, they would take us into the courtyard and shoot us against this little wooden hut I had seen before - built there in the middle of the yard for that purpose. They told me that if they opened the door and beckoned for me to go with them and they didn't have any bread to give me (a loaf or half a loaf of bread), it meant they were going to shoot me. If they handed me a loaf of bread, it meant that (surprise, surprise) a fantastic great bonus in my life - I am a lucky man because it means that I am going to be sent to Auschwitz or to any other 'star' concentration camp. So, bread handed out meant transport - concentration camp, to a new lease of life; no bread and it meant shooting. Funnily enough I was thinking now that I started ‘memorising’ this cell, like Greta Garbo in her great film of Queen Christina after the night she spent with her lover. Next morning with this funny and rather hypnotic music, she slowly walked round, touching everything. At a certain point her lover asked her what she was doing.

“I am memorising this room” she replied.

Little did I know then that several years later I would meet her at a dinner party for a German producer. I laughed then as I thought how life, or fate, always gave me film cameras. So I memorised this cell, not walking and touching, but watching and looking at it. I remember I saw some bullet holes in the wall. Somebody was shot in here. I saw a lot of inscriptions, little letters: ‘Here I am, I am dying tomorrow, please, if you meet my wife, Maria etc etc ... please, tell her that Marek was killed here,’ then the date and so on. My first night in the cell was empty and lonely, in spite of these two people near me. They both took the two beds with no mattresses, and I sat on the floor against the wall.

Feelings? yes, of course I was frightened, and of course I was expecting the worst, but somehow I was getting acquainted with this feeling, reconciling myself with the thought that this might be the end. I had to be prepared. There was one moment in the middle of the night when I suddenly started crying, yelping like a little dog, and it woke the two men (they’d both been snoring and farting in their sleep). The stench from the bucket was penetrating the air with a pain, like a knife, cutting the night in this little room, cutting through my heart.

They were very annoyed with my yelping. Perhaps it evoked their fear. Their panic.

“Don't do it, don't do it, we don't do it here” they were whispering.

I knew from them that they had already been in the cell for three or four days, but these were my first hours and obviously there was a tremendous difference in age - I was only just out of my teens, they were already grown men! The morning after my nightmares, I woke up with some kind of inner jerk and fear. I felt like I was hooked on an iron hook and hanging in the air with my limbs and my arms waving for help and yelling inside. Silently but yelling, I learned then how to yell silently. In the morning they brought our breakfast, some black coffee, a tiny piece of bread and a little piece of marmalade, a sort of little cube, a dice.

We ate this breakfast in silence and the Polish man made a bitter remark.

“Not yet, not yet our turn, they always shoot on an empty stomach.”

Then he started having diarrhoea again, moaning and groaning and shouting, yelling with pain. Suddenly I realised that I could hear a noise outside the window, a kind of constant boom. I realised that the plain in front of the building was being filled again with thousands of Polish people from Warsaw, waiting for their orders to their next destination. The next stage of their journey into the unknown - German metaphysics. As I was listening to this noise, I had an urge to pull myself up on the window bars and to look at this plain and the people. I heaved myself up and I saw them. Thousands of people like yesterday just getting orders to sit down. They were sitting down, slowly and with trepidation. I looked down and I saw a very strange scene. Two, three or four Gestapo officers standing underneath my window, almost on the steps leading to the building, as a matter of fact the same steps where I was yesterday where I was waiting my fate. In front of this big gate leading to heaven or hell. One of these officers looked familiar. I recognised him from the photographs which had been printed on leaflets dropped from planes on Warsaw. The famous General von den Bach. (General von den Bach was a man who was singled out by Hitler to conquer, to squash the Warsaw uprising, and he started the propaganda by dropping these little leaflets from planes). The leaflets said that if you decide to walk out of Warsaw, with your arms up, then General von den Bach himself will guarantee by his sword of honour, your safety into freedom. We all ignored these leaflets, they were scorned by the Polish people and nobody would leave their positions in Warsaw. I wonder now if it was all worth it, this indomitable attitude, I wonder now. So many thousands of people were killed within only 63 days of that Warsaw uprising.

63 days it lasted and it left all Warsaw dead. In ruins.

Some people are doomed right from the beginning; some people are destined to go through a life of luxury; some are destined to go through communism, and some are destined to go through the humiliations of war. I was born to be a minority. All my life as far as I remember, during German occupation I was anti-Nazi. In the communist regime I was a minority because I was anti-communist. I was always in a way, outside the law, always. Then I began a life as an actor, a jester. I never treated life seriously, even now in England I am a bloody foreigner.

As a matter of fact being always outside gives me a good warm feeling of my own dignity, consciousness, style and power. I enjoy being a minority, it gives me a force to act and I can hear my invisible film camera buzzing and floating above me. As I saw this face of General van den Bach, my force prompted me. It did happen several times in my life that suddenly, unexpectedly, I fell outside myself and I would watch my action, or hear my voice saying something that I couldn't help. It was me saying it, and yet it wasn't me. My inner force was pushing out of me an action that otherwise I wouldn't undertake, and yet it was me who was undertaking this action. I simply shouted to General von den Bach standing there down below. My German was very good, because ever since I was a child I spoke quite a lot of German with my mother who was born in Vienna.

Our parents taught us languages - French and German.

“Her Generale: - Ich bin hier immer ferchefted” which means “My general, I am still arrested here”

“Vardom?” - “Why?”

I used my full voice because of my urge to convey this message to him. He was in this moment the God of every single moment, of everything that was happening, moving, jumping, dying, crying, smiling, laughing, making love everything - he was the God of everything. The General was surprised, he looked up, yes he was looking up straight into my window - he was looking at me!

Then I heard him saying towards me.

“Ich come gleich drauf” which meant ‘I will come up immediately.’

At this moment I heard a yell behind me. My two inmates were trying to pull me out of the window, shouting.

“What are you doing, you stupid little bastard, you stink, you idiot - they are going to kill us all immediately, how dare you.”

They pulled me back and down onto the floor. They started kicking and hitting me, and spitting at me. Finally they got tired, and I was just sitting there like an idiot, waiting.

What was going to happen?

After a while the Polish man asked with trembling voice.

“So what … what did you say to him?”

I told him, and he replied puzzled: “What did he say?”

“He said I'm coming up.”

“And this was General von den Bach himself?”

“Yes” I said, “he looks like a squashed frog, he's got round thick glasses on his round puffy face, I remember him from the photographs on the leaflets they were throwing from General von den Bach, I'm sure.”

“And did he say he was coming?”

The Polish man couldn't believe it.

“Yes” I said again, “he said he was coming up.”

The men smiled, full of hope, perhaps there is hope for all of us.

In a situation like that when you are in a condemned cell, you start clutching at straws, you start believing in all possibilities, and experience feelings of optimism. You start telling yourself little stories that enable you to smile, and have a positive outlook on your future. They thought I had saved their lives and perhaps the general would free all of us. Then, as if in answer to their silent thoughts and prayers, the door started opening with all the same horrifying metal hard clinks and clonks and clanks, and there was my officer who arrested me yesterday. There was no dog this time, just Gestapo soldiers; he pointed at me and beckoned at me to go out. I looked at his hands, no bread. So I turned to my friends, and by this time I felt sorry for these two men.

“God bless you” I said.

They just looked sadly back at me. Then I was outside in the corridor and the door was locked behind me. I was led by my Gestapo man down the stairs and back to the same courtyard where he led me to this little wooden house. He asked me to stop against a little wall, it was riddled by bullet holes. Now I understood why they built this house. After each execution they would change the wooden planks. Behind these planks on the other side there were presumably sacks with sawdust to muffle the sound, and prevent the bullets from going outside and hurting the German people who were walking in the courtyard. We approached two Gestapo soldiers, and my officer spoke something to them in German, then he disappeared. Both of these soldiers had rifles and one of them handed me a piece of black material, a kind of ribbon.

“What is that?” I asked.

“That is something we give you here.”

He told me it was to be put around my eyes, because they were going to shoot me. It sounded so normal, so incredulous, so ludicrous that I didn't grasp the meaning. I always thought that if by any chance one day I would be in front of the execution squad as I was then, I would look at the sky, I would say goodbye to the world. Some kind of music would play inside me or for me, or perhaps I would pray to God, or perhaps I would shout: “Long Live Poland.”

But nothing like that happened, absolutely nothing, just a complete emptiness, a void with no feelings whatsoever. The only thought I remember I had was that I didn't want to feel any pain. I wanted it to happen instantly so I just dropped this cloth, this piece of material on the ground. Then one of the soldiers spoke to me.

“Ready?”

“Yes” I said, and I still couldn't grasp it. I couldn't comprehend it, it didn't register inside myself, inside my system. Then I saw them aiming at me, and a voice behind this little wooden building would say “Ein” they were getting ready and taking aim, “zwei” (which means two) and “drei” or three, obviously when they got to three they would shoot.

But before they got to three, there was a long long pause.

Then suddenly these two soldiers started laughing loudly.

After the laughter I looked at them. I just didn't understand it.

I replayed in my mind scenes from films I had seen. In one I saw Marlene Dietrich (in one of her first films) when she was before a firing squad. As they were taking aim she would put lipstick on and look in a mirror to make herself more beautiful. With complete contempt for the German soldiers, she would simply ignore the execution squad - or she would have a cigarette, she would take two puffs and then she would say in her German accent.

“I'm ready.”

I suddenly saw all those little scenes from the films. Then it started dawning on me that this was it; this was the end of me.

Then this hidden voice, once again, he shouted: “Ein, zwei.”

Again they were aiming at the ready to shoot and before “drei” (three) again they had a good laugh. They repeated this three times. By this time I realised that I had no energy left anymore in my muscles, and my muscles simply gave up. I felt I was sliding down along this wall and I thought this is what it looks like, what it feels like to die. I didn’t feel any fear, but I am giving in, I am giving up physically. I can't bear it any longer, I want to die. A psychologist once explained that death is very much the feeling of human nature. In certain circumstances you feel that its unavoidable, you've got to die. You stop being frightened, you want death to happen as soon as possible, to close the chapter. It is simply a need of nature, so I felt like that.

Suddenly, this voice from behind the little wooden house shouted.

“Get up. Enough.”

My officer appeared, again with the dog, and I realised it was he who was giving the orders.

For the first time he looked directly at me with some kind of smile I saw on his face. The first time I saw him looking at me. He spoke to me in Polish again: “Follow me.”

I followed him to the big front gate, which opened as we approached. I stepped out of hell with him and once again into the outside world, into the blazing sun and the crowd of people sitting there. I could feel their eyes upon me, looking at me with great curiosity.

Then he pointed at the crowd of the people and he said to me, again in perfect Polish.

“Will you please join this crowd of people, sir.”

He was calling me sir (or zee which is the equivalent of sir in German).

I didn't move because I didn't know the meaning of it. I didn't understand, the penny didn't drop.

He spoke again.

“Well, I am not going to repeat this a third time, but I will repeat it a second time, will you please join this crowd of people - you're free.”

Then I understood, now the penny dropped. I walked down the steps, those few big steps, got back into the crowd of people, and started submerging myself. Diving down, trying to get myself as small as possible - smaller and smaller and smaller. I think I should be like a mushroom. First cut the head, then the stalk and make it shorter, and shorter. I should be cut down into a tiny little size, finally to become grass. Again I smelled the aroma of the grass, and I touched it once again, and I thought why can't I be this grass, this blade of grass, all this grass here? I was almost sniffing with my nostrils on the ground, imagining myself to be a small as a speck so that nobody could pick me up and once again put me through this ordeal, this torment. As I was sitting there, almost in the same place as I had been yesterday, in the golden glow of the sun I became a nobody. I had already disintegrated completely into nature, or at least that was how I felt.

Suddenly over the loudspeaker came the order.

“Everybody up.”

Slowly, we moved along the streets of the suburbs of Warsaw - through streets full of burned empty houses. I realised that looking through the windows of these houses could be horrifying and frightening, because windows without people inside, the staircases without people inside, are houses which are haunting and haunted. Along these haunting and haunted empty streets of Warsaw, the thousands of Warsaw people, we the Poles were pushed away, step by step out of Warsaw. Although I couldn't believe my luck and my happiness, I was still a prisoner. Still under German occupation. I felt free once again with a strange sense of freedom, even though we were all looking back at Warsaw. We could still hear bombs exploding, and of course we could see the heavy clouds of dark smoke above the city. We thought about Warsaw being slowly annihilated, bit by bit and people dying. Many of us there had tears in our eyes. Eventually we reached some fields filled with onions and tomatoes. I remember the people running into the field with great joy and the Germans didn't pay attention to it. Rather than sleeping, we were eating tomatoes and onions because for so many weeks we didn't have any vegetables or any vitamins. There was the urge to bite, and get into our system some fresh fruit, fresh vegetables. It is incredible that I remember this so well. I was eating fresh smelling tomatoes, onions and cabbage - everything that was green and everything that was fresh, everything that was made by God.

Later, we reached a train station. It was a slow journey, and from the station they pushed us into a train and within 20 minutes or something like that, we were in Prushkov, a temporary concentration camp situated on the premises of some sort of disused factory. It was a huge building like a plane hangar on two or three floors. It had huge empty rooms and a staircase and people were just lying there waiting for transport by train. There was another train station just next door to it. The misery was unmistakable. People were crying while other people were eating, some were cooking something on the floor, having created some kind of cooking facilities. The whole of the German occupation made us Polish people very loyal towards each other and we felt like one entity, one organism. We felt the need to help each other, so the people would share their pieces of bread, their food, their everything in Prushkov, in this concentration camp. Then suddenly I heard somebody calling me by name, Vladek, or Vwadek in Polish. I looked back and I recognised the man immediately - Staspoznanski. He was much older than I was, and I remembered he had been a pupil of my father’s. Staspoznanski was with his very beautiful young wife, a beautiful woman. He told me that we should stick together as another friend, Fradek, was there also. So we found ourselves in this camp knowing that on the next day we would be pushed into the train transport - of course it was the great unanswered question - where would the transport go? We nicknamed Staspoznanski, Stasz. He was in the underground resistance, and was a very experienced man; he knew how to survive, everything. So he immediately became a kind of General, our Commandant.

“Look” he said, “we've got to watch where we are, we've got to stick together by all means. Presumably there was pandemonium in front of the train, but we've got to stick together and so we've got to watch where we are going. I've got a compass with me which is hidden, if the Germans search me they wouldn't find it, and we will see if the train is aiming towards Auschwitz or towards Buchenwald, towards Germany or wherever and accordingly we will act. Either we will go further by train, or we will try to break the walls and jump out if by any chance there is a danger that we are aiming towards Auschwitz - ok?”

The next day we ate something, and then the huge hall filled with people. We were ordered to get up and go out to the nearby station. When we got there we saw cattle trucks. The Germans started selecting people in a very brutal way, and then they would count them. I can't remember how many people were selected for each truck. The trucks were filthy as you can imagine; the conditions were absolutely appalling. Stasz decided to smuggle his wife aboard (again the old Partisan, you know?). It seemed that nothing could stop them being parted. He had her wear men's clothes and hid her hair under a huge French beret. She didn't wear any make-up, and she tried to assume the walk of a man. As we were just reaching the big sliding door of one of these trucks and getting onto it, a German stopped us, shouting.

“Aus, aus, nicht ein mann?” - 'You are a woman, you are not a man.'

Stasz pulled her inside the wagon to hide her, but it was too late and this German pulled her out and I witnessed one of these scenes which were everywhere on the station, of people being parted, people crying and children being left by their mothers because they were pushed by the Germans into one train, and the children into another one. She was very brave as this German soldier pulled her out. There was no way Stasz could do anything about it. He just shouted after her.

“God bless you, we'll see each other again.”

“Yes” she shouted back at him as she was pulled by the Germans in a different direction.

Stasz found his wife again after the war, and they lived in Warsaw with two children. Stasz died a few years ago, but she is still alive. She was here in London, a very beautiful lady. So, we were locked in this cattle wagon - there was no room to sit down because it was so crowded with people, and then the journey began. We were travelling along and stopping every so often. Some people were praying, some were defecating and farting. Others were hating each other and quarrelling, while others were loving each other and helping each other where they could, it was pandemonium. Dante’s inferno - totally encapsulated and made by the Germans here as if they had waved a macabre magic wand to enact itself again. Stasz, with his compass, was by a tiny little window watching the terrain, the landscape and checking up the distance. From time to time, he would say things to us.

“Now watch this next turning, if we turn to the left, we are definitely going to Auschwitz.”

But we turned to the right, and then we turned right again, and again. Then we headed north, Stasz continued: “I am sure they are taking us to Skinomind.”

Skinomind is in East Germany, and because he was a partisan, Stasz knew the place in which they had already started producing the V1 bomb. He already had news from the headquarters before the uprising, that the Germans had started preparing some sort of new weapon. Indeed, the more we were getting into the landscape into North Germany, the more we saw through the chinks in the cattle wagon, big holes in the road from bombing. So Stasz, a knowledgeable man, told us that the allies, that the Americans were bombing. The holes here looked quite new. About three days later after our trucks had been loaded onto a train, we continued to travel along, quite slowly. An alarm would suddenly sound, and we knew the sound quite well by now - the sirens for an air raid. The train stopped but they didn't unlock the trucks. We saw the Germans running away to the field and lying down. The planes passed by, and we prayed for them to start throwing their bombs. Although we were in danger, we still had this fighting spirit inside ourselves. After the air raid ended, we continued on and stopped at the next station, and here an incredible performance took place. At the front of the train the Germans pulled us out in their usual brutal way - with typical shrieks and shouting. On the road at the other side of the station were lots of trucks such as the big lorries. They transferred us from the train to the new lorries, and on the way we had to go between two rows of German women who would spit at us, and point at our cattle trucks. We noticed with a shock that the trucks had the words Polniscz ban bitten von vashav (or Polish bandits from Warsaw) written on the sides. So these women spat at us, kicked us, and shouted invective and abuse.

“You bloody ban beaten, the Pole and ban beaten from Warsaw.”

We looked at each other, and Stasz told us that the soldiers were indoctrinating these women. We are bandits to them, we are not fighting our cause, we are the ban beaten. So that was it. We were transferred to the lorries and Stasz, Fradek and I managed to be on the same lorry. We travelled on, along smaller lanes. I must say the landscape was absolutely beautiful, and perhaps because I am Piscean, and secondly perhaps because I am Polish, I really never give in. I always have this power, this incredible resilience and feeling that I have to start again. I have to once again dust myself down and pick myself up and go into life. I wonder if I still have this spirit - for so many things, including my career as an actor in this country - have broken this spirit.

I was watching myself last night on the television in the film “SPYS” with Elliott Gould and Don Sutherland - big film stars, and I was playing a funny part. I was really funny, and it was made in 1974. I quite liked myself in that part, I was very elegantly dressed and I was the Russian Ambassador. I was thinking, Christ, downstairs in the kitchen, there is a tape waiting for me, steaming and oozing the story of the concentration camps and here upstairs watching myself, I am screening with the big Hollywood film stars.

* * *

Chapter: Five

After several hours journey, we reached a kind of crossroads. Certain lorries were turning to the left, directed of course by the Germans out on the road, and certain lorries were being directed to the right. We were directed to the right, and Stasz told us it was okay as we would be going north. After a few more hours, evening settled upon us. Again this beautiful end of September and it was already cold in northern Germany. We crossed some kind of incredible bridge, not above rivers, but above the sea - it looked like the sea, and everywhere there were holes in the ground from fresh bombing. Finally we reached a field and I will always remember it, and the crowds of people upon it. The Germans always collected crowds of people, then disposed of them. Here, we had to disembark from the lorries, holding onto each other all the time. Stasz had instructed us that we all had to stay together, no matter what happens, we've got to be together. People were sitting on the grass, again under the sky. We knew that we would spend the night there because of the gossip, and little stories that go on always in the camps and in the crowds of people - it was incredible; there was always somebody who knew best - there was always somebody who had overheard a conversation and whatever. So this was the evening in which they brought us all some kind of soup. Actually it was the water (which I’ve mentioned previously) with a few floating beetroots in it. I have to say that the Germans were organising these things absolutely perfectly well. In no time they distributed to the crowd of thousands of men (only men were there), pieces of bread and soup and then suddenly again I heard somebody calling my name - Vladek. It was Mr Goshinski [*] who was a Polish Jew, and during the German occupation, he and his two sisters were living not far away from us in Warsaw. His wife Frena was the daughter of the very famous Jewish film director before the war: Polidenski. So this Kosdjienski [sic] was there, and he called over to me, saying he was very pleased that we could see each other. In these camps people would make pacts so that if they got out and we didn’t, they would tell our families what happened, that you saw me in this and this place in the Pomorian fields. Pomoria was the district where we were then. So many people asked me to do these things during my journey through this darkness of Germany. Then we had to sleep, so we cuddled each other, literally. There were no improper things, just people warming each other's bodies. We cuddled together, embraced each other like that and tried to assume the most relaxed position to create as much heat as possible. That is how we went through this night. In the middle of the night I would wake up and look at the sky. At a certain point I saw Stasz doing the same thing, and I knew that he was thinking about his wife, and Poland, the war and the Germans and everything. Even with this tremendous gigantic power of destruction rolling like huge tanks over our heads and our bodies, there was a beautiful sky at night with September stars in the middle of northern Europe.

In the morning, the Germans started organising us. They started calling out professions, such as painters, carpenters, locksmiths etc. This was towards the end of the war and they needed specialists to work in their factories. This created chaos among all of us, because some people were very willing to say: “I am a carpenter” in order to get out of the degrading work, because the next step after this could be the crematorium. Nobody knew what was going to happen next after this stage, or the next minute. I had a great temptation to say that I was a photographer because I knew something about photography, and Stasz warned me not to do that, we must stay together. Koszinski* decided to enrol himself as a carpenter, so finally he said goodbye. He was sent to a factory in Germany and he worked there. He survived after the war and so did his wife, I think they had a son.

EDITORS NOTE: * It is assumed that Mr Goshinki/Kosdjienski and Koszinski are one and the same person - merely spelling is changed as Vladek alternates between languages.

After the selection of craftsmen was completed, the rest of us with no jobs were pushed into several lorries. We went still further north into a beautiful pine forest with sand dunes near the sea; you could smell the sea, and seagulls were flying above us. I was always looking at the birds and flies and thinking, why wasn't I a fly? - why can't I fly out of this hell? - why am I not a seagull? You have a curiosity of nature - you think certain parts of nature are involved in making death. Even in this death making camp of German Europe, certain parts of nature are still free - like the seagulls and other birds. We arrived at the barracks and that was it, that was our concentration camp. We were selected into barracks, hundreds of us. We were hundreds of Poles from Warsaw. We were shoved into this big corridor, I think there were about four rooms on each side, and a huge latrine with the holes in the floor (for defecating) at the end of one. In each room in this house we had straw bunks on the first floor and the ground floor, and that was how we were left to sleep. We were very much aware that we were completely cut off, and as I was the only one who really spoke German, I overheard the Germans, our guards talking from behind the barbed wire. This place was called Fernichtungslager - (Fernichtung in German means to exterminate, to annihilate) - so we were already dead. Soon we realised we were only being kept alive to do some very useful work. We were brought into the most dangerous spot which was bombed quite often and we were pushed into the front lines; they didn't even make a list of our names. Even in Auschwitz they kept some kind of files. If somebody died for instance, the Germans would send a letter to the relatives saying the person had died of pneumonia, when in reality he had been battered to death or whatever. So here in Fernichtungslager we didn’t even have our names. Over on one side of the barbed wire fences were the French prisoners of war, and across the other side near to us were Russians. The Russians were treated in the most appalling way, much worse than we were. They were simply starved to death. I saw them eating the earth, literally, because they were so hungry. They would eat earth and then they would die in contortions, in pain, yelling and praying, cursing. Stasz was a conspirator, and he had his methods and knew what to do; he knew best. Knowing that I spoke French very well, he immediately arranged that I would get in contact with the French prisoners of war. They were being treated much better than we were, and it was arranged that I would hand them a list of our names so that if we died and the war ended, final judgement would be proclaimed and pronounced upon the German people. Our names would be added to the accusation with our dates of birth etc so that people knew we died here. So we made the list, and I passed it to the French prisoners of war after Stasz undid one plank in the latrine close to the few taps providing cold water. On the other side were the latrines for the French. I spoke to one Frenchman and I gave him the list - that's all we could do. Then we knew that we were in Fernichtungslager - the camp for the dead - people who were already dead and thus our lives began.

The Germans would take us in the morning when it was still dark. We were always put in groups of fives, and after breakfast we would march. Breakfast at least was hot - some kind of tea, coffee - imitation water. We were given a piece of bread, marmalade and margarine for the whole day. Some people would eat the food immediately, some people would keep it and would bargain with other prisoners; trade was going round. Some found mushrooms in the forest, but not even knowing if the mushrooms were poisonous or not, we would trade them for a piece of bread. The hunger was unbelievable. For the first time in my life I realised what hunger was. Physical weakness set in slowly upon us, and morale needed constantly boosting. Stasz helped greatly with this. For instance, there was another man whom I remembered had the corner bunk on the first floor of this stuga (which means room) in our denomination of this house, and he would read in the evenings; he had hidden on himself a little book on Polish poetry. Stasz would speak conspiratorially with him, then he would come back and tell us that the man was a Jew, and that he was afraid that someone, out of spite, or being degraded by the Germans to the animal level, would, in order to gain some favour from the Germans, perhaps a little piece of bread to appease this appalling hunger, eventually point at him and say he was a Jew. Indeed there was one man that we were very much aware of. First of all, he was very near me when I was sleeping on my bunk and he would masturbate very loudly, and he would talk about this being the only thing that he was left with. He was fat, he was awful. We were put together with the worst element - lower middle class on Warsaw - the people who spoke this foul language who hated intelligencia, yet Stasz and I were from the intelligencia, and they depended on us because we knew better and we could lead them into something, into freedom or into living better, cheating the Germans. On the one hand they very much respected me for that, and I was the youngest one. On the other hand they despised me for the fact the orders from the Germans come through my mouth. I was being used as the dolmeitscher, the interpreter. This fat man started saying things like: “We know we've got one Jew here, and we will know what to do with him.” So Stasz had a conference with him and the other prisoners; they decided just to scare him. They said they would club him to death if he squealed, if he squeaked a word about this man. So again a loyalty between us developed, but I was so frightened of this man, and I slept very near him. I found a wooden club in the forest and I slept with it, in order to defend myself in case he attacked me. I had incredible dreams as I was falling asleep, knowing that I only had a few hours to sleep. In the morning the Germans would yell, and immediately we all had to get up. We had to stand up and wait for the Germans to come to inspect, to count us. Then we were allowed to go to a cold water tap for a wash. Stasz's instructions were always that we should shave under this icy cold water, and wash our bodies in the evening after coming back from work. The Germans kept cleanliness in this barracks. They were paranoid about disease, especially about tuberculosis (which later on proved invaluable for me to penetrate this fear in their minds and helped me to escape). Later on, hunger got hold of the fat man and he became a very humble and a very different man. He kept closer to all of us because he knew that only in closeness could he gain some injection of something positive into the mind. I also remember the corridor would be cleaned once or twice a week with water and some kind of suds, I don't know what it was. I remember that one morning I was delegated to clean the latrine. There was all this faeces floating on the floor and blocking the holes. I had to unblock it, and this German was standing almost on top of me giving the orders. I remember the first time I did this I threw up, but one gets used to everything. It was unbelievable, I was wading in this mess, and with my bare hands I was unblocking the holes, then taking these lumps of stinking wet faeces to a wooden barrel and taking it outside. The guards took it to their quarters to nourish their fields, hoping that the next spring it would mature as manure. I didn’t have any feelings of disgust towards the dirt and mess as you may imagine. Instead it became part of life, part of living and we tried to keep it as clean as possible.

* * *

Chapter: Six

We would be marching until it was dark, and as we marched near the barracks, near the German quarters, we would become aware of the smell from the Germans urinating. We would steal from the dustbins, and one would steal anything that was there. Just one split second, you opened the bin, your hand went down and you dug out whatever was there. I remember once I dug out fish entrails; fish guts, which were smelly. I kept them on me, in my pocket all day when we were working in the forests. I brought them back in the evening, I washed them and I shared them with Stasz and Fradek. Our little meal was absolutely delicious, but then of course we had diarrhoea. Stasz was very clever in his methods of survival, and I was grateful for him being there. I was more emotional than most and people are not used to these things, but I was the youngest one. I remember my phobia about barbed wire; I couldn't bear it. I would walk outside the barracks sometimes when we were free, and just look at these wires. I would think that they would disintegrate, and that I would be able to walk across the fields somewhere into freedom. I remember once that a pigeon perched on our windowsill. All of us started watching this pigeon, it meant ‘bring us luck, bring us freedom.’

In the forest the Germans had camouflaged the barracks. It was our job to build big halls with blocks and bricks, presumably for storing the V1 rockets - although we never saw one. The Germans never showed us anything that was deep inside the forest, but we were building these barracks. My job was to carry bricks on a wooden contraption which they put on my back.

After the first day of work I suddenly broke down and I started crying. All the prisoners were just looking at me; nobody said a word. Stasz and Fradek were far away, and one of these older men who was also a prisoner, said: “Don't do it please, it won't help you, it won't help us. You've got to develop toughness, that's all I can say.” I will always remember that. I remember too how they treated us. For instance, when they discovered that I took one brick too few (we had to carry five or ten at a time but I don’t remember how many I had on this occasion), they would beat me with a wooden club, asking me to take off my shoes.

They would beat my heels, and later I developed gristle in my heels which gave me tremendous pain, and that is how they injured me. It healed unevenly, and later I had to go to Krakow to see my uncle, a surgeon. He had to operate on me because I couldn't walk, he had to straighten this gristle or scrape it off. After walking about half a mile I used to be in pain, and to this day I cannot walk properly on flat shoes or barefoot. I have to wear heels which have been slightly raised. The Germans would frog-march people, shouting at them to jump in a crouching position, this way, that way, backwards, forwards, backwards, forwards and that is how they were killing some of the weak people. We would see some of them dying on the spot of a heart attack, these people would just be clubbed and frog-marched and made to jump like an idiot up and down. When these people inevitably died, we had to bury them. We had to bury them in the sand dunes and I remember people saying: “I don't want to be buried in this sand, I don't want to go underneath the sand, I want to buried in the proper earth.” This was another thing - the urge to be properly buried. I started to understand this. First of all you wanted to die in your own country, and be buried properly like your fathers and grandfathers and great grandfathers. You wanted to go through the same ritual. Human nature is very very funny in that you get accustomed to certain things and you don't want to give them up, even when facing death and destruction. Then I remember the bombing in the air raids. We were always very jubilant about these, though of course we couldn't show our feelings to the Germans. They were petrified when the sirens started wailing, they ordered us to abandon our work and to run with them. Although we were jubilant, we were also in fear of the bombing, we were all equal. The Germans would run with us to the forest and lie down under the trees. The bombing was never near us, it was happening further away but the allies knew exactly where the bases were for the V1s. We did not suffer explosions where we were based.

We camouflaged the barracks that we were building very carefully with trees that had been cut down - with branches and leaves every evening, so that the next day from above, it still looked like a forest. The forest was beautiful and this was the source of some of my positive feelings from this concentration camp. The intake of oxygen and the smell of the sea. Seagulls were flying overhead and were constantly calling. The forest in which we were working was a pine forest.

I still feel the need of this smell in England, especially when the sun is shining. In Scotland they have pine forests, but here in England we don't have any pine trees.

September gave way to October with beautiful weather all the way through, and in the forest we saw animals, rabbits mainly. Sometimes we managed to catch them, and even eat them raw with all the entrails and everything. Stasz with his 'survival kit' helped us use the skins to make gloves, however clumsy they were - just to cover up our hands, with the fur inside. We found mushrooms too, which were fantastic. We would also pick up lots and lots of twigs so that we could make a fire in our barracks. We had a little iron stove with a big pipe to take the smoke outside. We were allowed to cook a little in the evening, so we had some things out of tins which we had found. The world is full of treasures lying around you, but if you are spoiled like we are now spoiled, you don't see them (I am now here in this lovely warm kitchen of mine). When you are induced like an animal to fight for your life, every scrap of metal, every nail on the ground, every twig, every tin thrown away from the kitchen you use and you treasure. You wash it very carefully and you make soup, mushroom soup. The inventiveness of people is incredible. I remember we invented unbelievable tools, one of which was a wooden pole, at the end of which was a little nail. You would carry it with you and use it as a fishing rod, for fishing from dustbins. Wherever there was a dustbin, you would simply ‘fish’ some great treasures for eating or storing, as you passed by. I had many things under my bunk which were treasures. Some of them were stolen; some of them were traded for other things. So this was the life in our concentration camp. The fat man always used to play with himself during the night and I remember thinking, Christ, he has the energy to think about sex. I was devoid of any thought of sex. The driving force was to keep alive. You always thought of that, that and what could you eat? – things like that. My methods were different from those of Stasz. His were to survive; he was trained like that. I wasn't trained at all; I was always going by instinct. My instinct was to run away, to escape. He knew about this because we had been talking about it.

“My God” he would say, “you will land in a gas chamber, or in a furnace somewhere, Germany is riddled with concentration camps. You don't have to go to Auschwitz to be burned; try to survive.”

I would say to myself, no I prefer to be killed, but at least killed while I was running away, while I am in action. I could not stand being inactive, giving in. So I started building up slowly, little by little, the possibilities - dreaming out my possibilities of escaping. I always was a dreamer ever since I was a child; I was different from other children. I would talk to the flowers, I would dream up incredible stories. Every five minutes I would be somebody else. I know the pain of being a fish, I know the pain of swimming into the deep murky waters and staying there, hiding. I am so susceptible to surroundings, to the environment. They affect me so much, that all my life pain is with me. I know the pain of walking from one room to another, because I have to shed something behind me, and I have to leave something different in this room, and I have to put on something new in this or that room. I know the pain of talking to different people. Every person affects me with his or her personality. I know the pain of listening to different music, that's why I don't have any music in my house. It is silence, because music immediately directs me, originates the feeling that it is in the music, not in me. I have to listen to the music inside myself. It sounds terribly highbrow, but perhaps that is the only explanation I can give. I go through pain talking about myself – a self-defence mechanism as they call it in England. When I stopped just outside my concentration camp, my little lovely kitchen, I made hamburgers with mincemeat and egg and breadcrumbs and onion. I put them in the fridge and they are waiting to be fried. I am going to have supper very soon - ha ha.

I remember that one day the Germans sent me to the kitchen, their canteen kitchen in which they were preparing our 'meals' - our watery soups and pieces of bread. The canteen in which they were cooking normal food for the Germans, those who were working on the V1 site and guarding us. The smell from the kitchen was absolutely marvellous. There were three fat cooks, all German ladies. I was asked to clean potatoes and as I was sitting doing this, I was stealing the potato peels. These were a great treasure and I put them into my pocket, thinking that we were going to cook some fantastic soup in the evening. I was going to share it with Stasz and Fradek. Suddenly I saw a piece of raw meat, a piece of pork. One of the cooks was very hard with me. She never smiled, she knew that I spoke German so she would give me orders - do this, do that. I had to run some water into the buckets and I had to wash up things, but when I saw this meat, I couldn't think twice and it disappeared. My hand just went towards it, covered it up and it disappeared in my pocket. This fat cook saw it, she came up to me and started hitting me, putting her hands into my pockets and taking everything out, including the potato peelings and shouting at me.

“You bloody Pole, you bloody bandit from Warsaw.”